One of the most important forms in Ottoman “Dîvan” poetry is the “ghazal”, written for an abstract beloved. Originating in Arabic, it has spread to diverse countries, but attained its highest success with Persian and later became a major part of Ottoman poetry, where Persian was the language of choice for poets that were part of the intelligentsia of that time. It is similar to the 14-line sonnet in English poetry, but has 5 to 15 couplets. It is natural to think that the “beloved” which is the addressee of the ghazal is a - maybe imagined - woman but research has shown that the beloved here is abstract but the notion of beauty here is masculine. This concept of beauty does not meed to be about sexuality, but it also does not need to be about a woman either.

Perhaps because of all these, the beloved is treated as a legendary being who is far away and as such can not be attained, and this resulting in the poet suffering the pain of unrequited love. It is also a known fact that Ottoman art traditions of the era does not tolerate poets to deviate from the traditional - mirrored by other art forms such as decoration (nakış). Thus new artists should not have a style of their own, but they should imitate earlier masters perfectly. This was one of the reason Ottomans looked at Western art with suspicion for a long time, seeing that each artist had a different style and did not necessarily copy the style of their peers and masters.

When looking at Ottoman poetry of the 15th century, the position of women poets becomes a little bit debatable. Male poets have to stay away from physicality when writing for an abstract beloved whose beauty standard is defined as a young male and they have to define love as a spiritual, platonical love (even if they themselves do not see love as such). But for the few women poets in Dîvan poetry, the situation could be different.

One of the most famous of these women poets (but relatively unknown for the general public) is Mihrî Hatun. It is certain that she lived in the 15th century in Amasya (a city that was the centre of education for young Ottoman princes) and she was the daughter of the kadı (judge) ot the region. Unlike women of her era, she had a good (private) education and learned Arabic and Persian very well. She channeled her skills to poetry and wrote poems that could be compared to the prominent male poets of the time. Although she was scorned - via poetic means - by her male colleagues this was not an issue for her. An important point is that she never hid the fact that she was a woman in her poems, in fact she was courageous enough to deviate from the norm (of writing for an abstract, but supposedly male, beloved), constructing poems using the language that her gender requires. It is normally expected a woman poet, regardless of how good she is, will quit writing by the time she gets married. For example, Zeynep Hatun, who has written poetry at the same time as Mihri quit writing when she was no longer able to attend poets’ gatherings (the main means of sharing poetry among the intelligentsia of the period). But Mihri did not get married and has given all her time to poetry, thus eliminating this apparent restriction.

There are a few books about this interesting literary figure, but I think her life and art has not been covered adequately. One of the reasons might be that there is very little known about her life. Most of her work has survived (she has hundreds of ghazals), it is known that she did not marry. She has poetic duels with male poets (a tradition in eastern poetic circles), some male poets wrote derogatory poems about her.

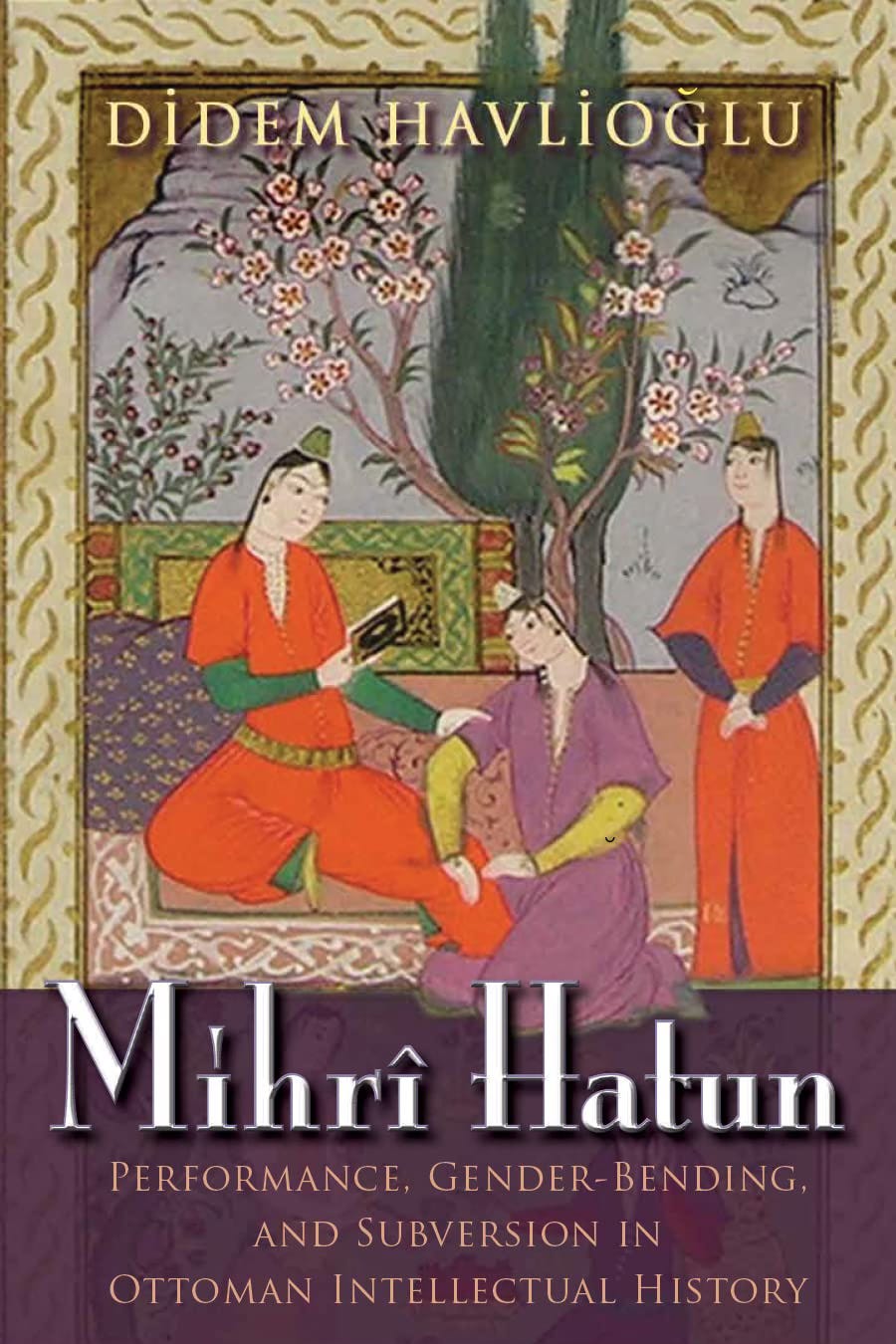

A book that covers the approach I briefly touched above has been published by Syracuse University. It is a book by Didem Havlıoğlu and has the title Mihri Hatun: Performance, Gender-Bending, and Subversion in Ottoman Intellectual History.

Going through the life and works of this relatively unknown 15th century poet, I can already imagine an exciting book or a marvellous film…