Brecht’s plays have always been interesting for me and I have watched a couple of them in my youth at various stages. Recently I have followed a book series with all of Brecht’s works translated, with various versions of the plays covered and with a lot of additional information.

During a business trip to London in 2014, I had some spare time and used it to see The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui.

Arturo Ui is a play Brecht wrote in Helsinki, while on the run from Nazi Germany and waiting for a U.S. visa. It was a period when he was trying to develop an alternative to Stanislavski’s Method (a technique where the player is immersed into the role and identifies with the role, down to actually living it in real life in extreme cases) for the Theatre Science Society. According to his personal notes, he has written the play in 10 to 12 days, but what is really poignant is that the play was never staged before his death.

Before I saw the play, I got the Ralph Manheim translation from Methuen. The book also had staging notes at the back.

I saw the play at the Duchess Theatre, close to Covent Garden. The text used in the play was adapted by Alistair Beaton from a translation of George Tabori and after successful shows at the Chichester Festival Theatre, it moved to West End in 2012.

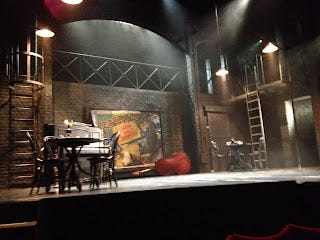

The fact that the ticket I got on the Internet was in the fourth row, just in front of the screen, made for a very good viewing. The stage that was prepared for the play truly reflected the atmosphere of gangster movies that Brecht always loved. There was also a “podium” that was used to keep the tempo of the play up and also helped players to enter and exit the stage. This podium helped the action in some scenes as well as helping some players prepare for the next scene and changing costımes etc. while others were already active on stage. I liked this mechanism a lot.

Ten minutes before the play started, a player came onto the stage, he sat down at the piano and started singing a jazz song from the era the play covers. Later, another player came onto the stage and started accompanying the first with a saxophone. In the following ten minutes, all of the players came to the stage, most of them playing an instrument and prepared us for the play in a jam session. I first thought these constituted the orchestra that Brecht always used in his plays, but when the play started, I noticed that these were the players. This certainly gives us an idea of how casting is done in the U.K. (Did they say ‘Playing an instrument is compulsory’ in the audition?) I must say I enjoyed those ten minutes a lot, independent of the play.

Before the play started, I noticed that a lot of promotional materials were being sold at the bar. There was the detailed brochure of the play, but also the book containing the script from Methuen (a little bit expensive at 10 pounds). I would have paid more for a book/brochure including practice notes or dramaturgy. Later, I was glad to have bought the book, since this was quite different from the Ralph Manheim translation I had and exactly corresponded to the version on stage.

The director - Jonathan Church - used some of the Epic Theatre techniques Brecht used in his plays, but the interpretation did not constitute a purely epic structure. At the beginning of the play, a narrator introduced all the players and provided some ironic information (as in the play text), emphasizing that we would watch a play but they did not use other typical techniques like slides, banners or declaring the events to the audience using other means. Some players have multiple roles and scene and prop changes happen in front of the audience under a dim light (but costume changes are not, contrary to Brecht’s suggestion). You can find an interview held with Jonathan Church during the play’s staging on the Chichester Festival Theatre here.

The players smoked on screen and nobody complained to the authorities (which is what happened in Turkey a few years ago during a play). The guns and machine guns used in some scenes were very realistic, with the proper sound and explosions, and this kept the dramatic tension high.

The play starts with Arturo Ui, who is an insignificant gangster in Chicago, offering protection to the Cauliflower Trust and using violence to show that he is serious. It continues in parallel with Hitler’s rise to power. Brecht indeed wrote the personages around Ui modelled on Hitler’s entourage. Ui’s second-in-command Ernesto Roma is Ernest Röhm, Guiseppe Civola is Joseph Goebbels, Dagsborough is President Hindenburg, the town Cicero is Austria, Emmanuele Giri is Hermann Göring. Henry Goodman, who has the lead role as Arturo Ui, portrays him in an amazingly intricate and layered acting. At the beginning of the play, Arturo Ui is portrayed as a comic guy, using gestures reminiscent of Charlie Chaplin in The Great Dictator (and maybe a trace of Mr. Bean). He is afraid of his own shadow, hides under the piano when the doorbell rings and talks with an exaggerated Italian accent reminiscent of Robert de Niro. When events unfold, he is more confident, he improves his speech through courses he gets from an ex-actor and he uses his body more effectively. Goodman masterfully transforms Ui into the greatest dictator and criminal that history has seen. Ui, who is laughable in the beginning of the play gets transformed into a tyrant that you would avoid in a dark street. The other players also give very good performances, but Goodman seems to have reached an important milestone in his career (see BBC’s article about the play). Ironically, a Jew (Goodman) is cast for the role of Hitler and as Ui strengthens his position, the play uses figures reminiscent of the Jewish candelabra, menorah, in Ui’s flags and the armbands used by his thugs.

In the end, Arturo Ui is a play to be enjoyed and watched with interest, staged with different approaches and techniques.